When I applied to medical school, the dean asked me, “Why do you want to become a doctor?” I told him I wanted to serve my community. He rolled his eyes, “They all say that,” he said. Clearly, he did not believe me. And in fact, after I graduated from Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, I took an academic pathway through residency and fellowship and into research.

But when I had to relocate from New York to San Francisco, with my husband, I thought about my answer and decided that I should put my research on hiatus and look for a position where I really could be of service to the community. I answered an ad that a “community-based program” was looking for a doctor, and submitted my application. Marie-Louise Ansak responded and hired me in June 1981.

Back then, On Lok had a newer facility at 1441 Powell Street, which was part of On Lok House, and an older one at 831 Broadway. Powell had a small office space and examining room, while the Broadway site lacked a proper clinic and was just a big day health center. There was something funky about it, and I later found out it used to be a bar.

In the back, a curtain divided the day room from a five-by-five-foot space where a nurse and I provided medical care. There was no hot water. Many of our patients had hearing impairment and sometimes, behind the curtain, I had to shout to make myself heard. It was very different from the academic medical center I was used to, where all resources were available. But we served people who really needed us and were so grateful for any care that they were given. It was a good place to practice medicine.

My experience as a medical student and a physician in training had not prepared me for the challenges at On Lok, but I was determined to make the program successful. I decided that the only way to make it work was to create a clinic practice. We had one public health nurse at the Broadway center, and two nurses at Powell, including a nurse practitioner. The nurses and the interdisciplinary team were the building blocks of On Lok’s PACE program.

Right before I arrived, On Lok’s only other physician moved out of the Bay Area, leaving me and the nurses with 248 seniors to take care of. Twenty-eight were living in nursing homes and two or three were in the hospital at any given time. I told the nurses, “You can partner with me to provide clinical care.”

At the time, the hospitalization rate was four to five times what it is today. Many elders went from the hospital into nursing homes. We needed to change this dynamic and shift the care from institutions back to the community. The day health center would become the center of care and, after a health episode, people would receive care at home.

This concept of community-based care was the foundation of the model, we just had to build the infrastructure to support it. It was a terrifying feeling because, when I was in training, people came to be seen in the hospital and if they did not show up, I didn’t know what happened to them. Now I knew who and where my patients were and I believed very deeply that they deserved the kind of care I knew we were capable of providing.

Our first goal was reducing hospital admissions. With a simple examination, we could catch seniors who were not well and treat them in our clinic before they got worse. Over a year, we cut our hospitalization rate by two-thirds. I then turned my attention to our seniors in nursing homes. When I visited them, I wondered, “Why are they here?”

There are three heartbreaking reasons why older adults who go from hospital to nursing home never return to the community: the family cannot take care of them; they lose their social network; or their landlord takes away their housing. If we could prevent people from going into the hospital in the first place, and then getting discharged into a nursing home, we could break that cycle. Instead, we would bring them to the day health center and clinic, then send them home with home care.

By January 1982 I was faced with a decision. I was planning to stay at On Lok only six months because I already had a research grant funded at a Bay Area university. Mrs. Ansak was very worried because if I left, what would happen to the seniors in our care? I went through agony trying to decide and reluctantly made up my mind to stay. I knew what I was doing was very compelling work, but I was also sad to give up a significant part of my life’s training and a clear career path to stay with a program whose future, back then, was uncertain.

So I went back to our nursing home problem. We identified eight people who could return to the community, and I proposed to Mrs. Ansak to open up four double rooms for them at On Lok House. Over 18 months, we brought all the seniors back into the community. We also rented apartments that could house participants who didn't have a home or family caregivers, and hired health workers to stay with them overnight. For seniors who were sick, we reserved two more rooms at On Lok House, where we began providing transitional care until we could either send them home or accommodate them in the communal living apartments.

Deinstitutionalizing people from nursing home care was a huge risk, but it was the right thing to do. One participant’s story will always stay with me. At 65, she was admitted to a nursing home after a stroke. Her right side was paralyzed. When I visited her one day, she was trying to peel an orange but nobody was around to help her, so I did. While she ate the orange, I thought, “This woman does not need to stay here.” So we moved her into On Lok House, where she lived another 25 years without ever re-entering the hospital.

It was a time of “heart and smart” at On Lok. We were determined to find a way to serve our seniors. We would try to prevent them from getting sick or sicker by providing for all their healthcare needs in the clinic, so they would not end up in the hospital. And we would prevent them from going into a nursing home by setting up a system of transitional care and communal living arrangement. All this was done to make sure they would remain in the community.

Within three years, we reduced hospitalizations and nursing home care, without increasing the death rate, at a cost 10-15 percent less than Medicare. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services recognized the program was cost effective, which meant they would pay for our participants’ medical and hospital care. However, Medicare does not pay for long-term care. In California, it is covered either by Medi-Cal or private pay. Mrs. Ansak was not fazed. “We will talk to Medi-Cal and have them pay for the nursing home care,” she said.

In 1983, On Lok began a three-year waiver demonstration to test its new healthcare financing system, in which a fixed, per person monthly payment from Medicare, Medi-Cal or private pay covered all care services for seniors who needed a nursing home-level of care. To do so, we had to assume full financial risk. The state of California required On Lok to set up a $1 million risk reserve fund in case we went over budget. That's when Mrs. Ansak and board members Dr. William Gee and Harding Leong took out a mortgage on their homes to satisfy the state requirement. In 1986, On Lok successfully completed testing of its model. Our history is all heart, mind, and courage like that.

Dreamers will always dream, and the dreamer in us said, if it worked in San Francisco, it should work elsewhere. Our aim was never expansion for its own sake but extending care to as many people as possible, while also pursuing policy change to ensure PACE's financial stability and sustainability. In 1987, with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the John A. Hartford Foundation, we launched the national replication project known as the Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly (PACE). In 1990, four new PACE organizations received Medicare and Medicaid waivers to operate the On Lok model. With the passage of the Balanced Budget Act, in 1997, PACE became a permanent provider type under Medicare and a state option under Medicaid.

The dream of bringing PACE to seniors in different communities was a reality.

I was able to return to academia and begin teaching in 1987. Mrs. Ansak asked Dr. Joseph Barbaccia, a current board member, to help me. I am grateful to Dr. Barbaccia, who sponsored my application for clinical faculty at UCSF School of Medicine, where I am now a clinical professor of medicine in the division of geriatrics. With colleagues, I have written and published over 40 research papers about On Lok and PACE. On Lok’s historical achievement in creating a Medicare benefit is now memorialized in the literature.

Ten years ago, I said to friends and family that if I were to retire then, I would have accomplished more than I ever imagined. Forty percent of all Covid-19 deaths in the U.S. were in nursing homes. By remaining in their homes, our participants experienced 75 percent fewer infections. Our initial vision of keeping people in the community worked, saving the lives of so many during Covid. When we started, we were working on taking care of our people where they had the best quality of life—in their homes and community. We did not know we were ahead of our times in our thinking and commitment.

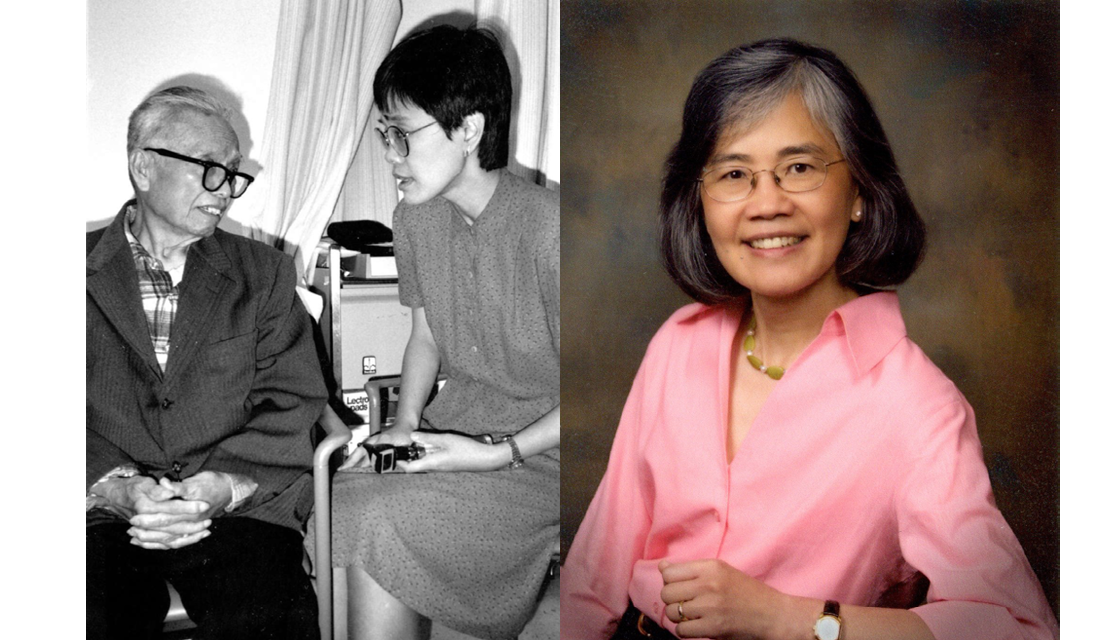

In the photo, Dr. Catherine Eng with a patient at an early On Lok health center, and Dr. Eng today.